Peer Reviewed

Sudden Hearing Loss Linked to Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Temporal Bone

AFFILIATIONS:

1Department of Otolaryngology, Lenox Hill Hospital/Northwell Health, New York, NY

2Department of Neurology, Southern Ocean Medical Center, Manahawkin, NJ

3Department of Radiology, Westchester Medical Center and New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY

CITATION:

Hersh SP, Hersh JN, Gerard P, Ali S. Sudden hearing loss linked to metastatic adenocarcinoma of the temporal bone. Consultant. 2023;63(4):e5. doi:10.25270/con.2022.08.000008.

Received December 23, 2021; accepted February 4, 2022. Published online August 25, 2022.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

DISCLAIMER:

The authors report that informed consent was obtained for publication of the images used herein.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Sheldon P. Hersh, MD, Lenox Hill Hospital/Northwell Health, 110 72nd Ave, Forest Hills, New York 11375 (sphersh.ent@gmail.com)

A 73-year-old man presented with a 1-week history of aural fullness and sudden hearing loss in the right ear. He denied any accompanying pain, tinnitus, facial weakness, or vertigo.

History. There had been no recent history of noise exposure, air travel, head trauma, antecedent or concurrent upper respiratory infection, change in mental status, or other past ear-related issues. His medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation. Of note, he was receiving pembrolizumab immunotherapy for stage 4 metastatic nonsmall cell carcinoma of the lung.

His current medications include tramadol, albuterol inhaler, ondansetron, folic acid, famotidine, lisinopril, atorvastatin, and metoprolol. He had a 12 pack-year smoking history and quit smoking cigarettes 30 years prior to this examination.

Physical examination. The external auditory canals were clear and patent, and both tympanic membranes appeared intact and clear. Audiometry (Figure 1) was performed at the time of presentation, results of which revealed a mild to moderately severe sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear and a profound sensorineural hearing loss in the right.

Figure 1. Pure-tone audiogram revealing a downsloping mild to severe sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear and a profound loss in the right.

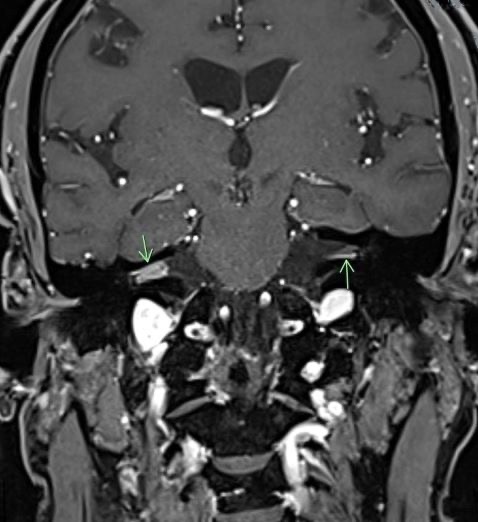

Diagnostic testing. Considering these audiometric findings, a 3-tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI-3T) scan of the brain and internal auditory canals was immediately conducted, results of which demonstrated an 8 × 4 mm enhancing mass in the right internal auditory canal, as well as 2 small foci of enhancement in the left internal auditory canal (Figure 2). Multiple areas of hyperintense signal were identified within bilateral cerebral sulci and cerebellar folia, which pointed to the likely presence of leptomeningeal disease (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images through the internal auditory canals. There is greater avid enhancement within the right canal than in the left with an additional focus of nodular enhancement in the left modiolus.

Figure 3. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted axial image reveals bilateral nodular leptomeningeal enhancement within the central sulci.

Patient outcome. Considering these findings, the patient was referred to his treating oncologist for further evaluation and treatment. He died 30 days later.

Discussion. In its “Clinical Practice Guideline: Sudden Hearing Loss (Update),” the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery provides an updated evidence-based approach on how best to diagnose and care for patients who present with sudden hearing loss.1 Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) is defined as a decrease in hearing

SSNHL may be linked to any autoimmune, infectious, traumatic, vascular, neoplastic, metabolic, or neurologic disorders (Table).3-5 Neoplasms represent roughly 2.3% of cases with vestibular schwannomas (also known as acoustic neuromas) accounting for the largest number.4,5 In a retrospective study of 351 surgical cases of neoplasms of the internal auditory canal, all but 15 cases (4.3%) were histologically proven vestibular schwannomas.6

Table. Reported Causes of Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss

| |

CATEGORY | PATHOLOGY |

Infectious | Meningitis, Lyme disease, syphilis, HIV/AIDS, herpesvirus, mononucleosis, Lassa fever, cytomegalovirus, mycoplasma, toxoplasmosis, rubella, mumps, rubeola |

Traumatic | Acoustic trauma, barotrauma, temporal bone fracture, perilymphatic fistula, otologic surgery |

Vascular | Sickle cell disease, cerebrovascular accident, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, cardiovascular bypass |

Neurologic | Multiple sclerosis, neurosarcoidosis, migraine, pontine ischemia |

Neoplasm | Acoustic neuroma, myeloma, meningioma, lymphoma, leucemia, meningeal carcinomatosis, regional or distant metastasis |

Immunologic | Behçet disease, Cogan syndrome, Wegener granulomatosis, autoimmune inner ear disease, systemic lupus erythematosus |

Metabolic | Metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism |

Otologic | Meniere disease, otosclerosis, enlarged vestibular aqueduct |

Ototoxic | Aminoglycosides, chemotherapeutic agents |

Malignant neoplasms of the temporal bone are an uncommon occurrence with an annual incidence of 0.8 to 6 per 1 million (0.2%) of all head and neck malignancies; most emanate from nearby cutaneous or parotid neoplasms.7 Rarer still are temporal bone metastases (TBM) originating from distant primary neoplasm, with an incidence rate that has yet to be determined.7,8 Despite the relative dearth of reported cases, comprehensive reviews of the literature7,9 and analyses of autopsy records10 have helped fill the void by providing an increasing awareness of and clinical insight into the often elusive and underappreciated topic of TBM.

Evaluating the postmortem records of 864 individuals with primary nondisseminated malignant neoplasms, Cruz and colleagues6 list 20 different primary malignancies that metastasized to the temporal bone. As described in both earlier and subsequent reporting, most of the primary neoplasms are epithelial in origin, commonly adenocarcinomas, with a well-recognized proclivity to metastasize to bone. The breast and lung far surpass that of other primary neoplasms in women, while lung, prostate, and kidney are the predominate neoplasms among men. These findings align with global cancer statistics that list lung, breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer as the malignancies with the highest rate of occurrence worldwide.11

Metastases to the temporal bone occur most often via hematogenous spread, although other possible means of dissemination have been identified.6 Direct extension from a nearby malignancy, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and leukemic/lymphomatous infiltration are all potential routes of dissemination.6,8,9 In leptomeningeal metastasis, tumor cells reach the leptomeninges and enter the subarachnoid space by way of either hematogenous spread or direct extension from metastatic sites in the brain.12 These cells then make their way through the central nervous system via the cerebrospinal fluid. Both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors may spread by way of leptomeningeal metastasis. The high incidence of bilateral involvement in TBM is a byproduct of the even dispersal of malignant cells when circulating through the cerebrospinal fluid.10

Symptoms associated with TBM may be influenced by various factors, including site(s) affected, unilateral or bilateral involvement, and whether metastases originate from solid or hematologic malignancies.9 In an extensive review of 255 confirmed cases of TBM, Jones and colleagues8 sought to identify the frequency of occurrence, the primary sites of TBM involvement, and likely symptoms associated with affected sites. The temporal bone is composed of 4 distinctive constituent parts: the petrous (medial), tympanic (lateral), squamous (superior), and mastoid (posterior). In a comparison of tumor histology with metastatic site, these authors calculated that the lesions involved in the petrous portion accounted for 72% of cases whereas lesions involving the mastoid, tympanic, and squamous sites were reported in 49%,16%, and 6.5% of cases included in the review, respectively.

The predominance of lesions originating in the petrous portion may be a result of its rich blood supply and abundant marrow. As blood passes through the petrous bone’s marrow cavities, its flow rate decreases when in the sinusoidal capillaries. This marked slowing of blood flow facilitates metastatic cell implantation and subsequent growth.6,8 Hematogenous spread may channel malignant cells through the petrous apex and may then move onward to other nearby temporal bone sites by way of osseous and perineurial spread.6,8 Osseous spread occurs in methodical fashion by moving first to the mastoid and then onto the tympanic cavity and external auditory canal. However, neural spread is a result of malignant cells gaining access to either the perineural and/or epineural spaces.6 Although the perineural and epineural spaces are anatomically distinct, malignant cells often pass simultaneously through both spaces.13

The symptoms most encountered in cases of TBM are hearing loss, facial palsy, and otalgia, while tinnitus, vertigo, otorrhea, and nystagmus occur less often.6,8 In an attempt to determine whether select symptoms are associated with specific sites of involvement, Jones and collegues8 did not find any association between site of involvement and hearing loss and tinnitus. They did, however, find a significant interrelationship between mastoid involvement, facial palsy, and otorrhea between otalgia and either petrosal or mastoid involvement, and between vertigo with petrosal involvement.

Asymptomatic cases of TBM have been found to occur in approximately one-third of patients, particularly when petrous bone involvement is present.8,10 When comparing the incidence of unilateral vs bilateral internal auditory canal involvement, Streitmann and Sismanis10 noted that asymptomatic cases occurred primarily amongst those with unilateral involvement.

Symptoms related to metastasis originating from solid malignancies may differ from those of hematologic malignancies. Unlike solid malignant neoplasms, hematologic malignancies (eg, leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma) are more likely to metastasize to the external auditory canal and middle ear, resulting in symptoms that may be confused with otitis externa or otitis media.9,14 These different metastatic patterns have been attributed to variations in TBM spread. Solid neoplasms spread primarily by way of hematogenous routes, whereas hematologic malignancies disseminate by way of hematogenous spread or leukemic infiltration.9

The presence of several select clinical symptoms and distinct findings on imaging studies point to the possibility of TBM involvement. Facial paralysis in association with cochleovestibular symptoms, bilateral involvement, and a history of malignancy should heighten one’s suspicion of the possible presence of a temporal bone malignancy.15 Imaging studies play a critical role in diagnosing TBM. Eliezer and colleagues15 listed several imaging features that, when visualized, underscore the likely presence of a malignancy within the internal acoustic meatus. Bilateral involvement, rapid growth on repeat imaging studies, high signal of the lesion in question on diffusion-weighted images, leptomeningeal enhancement, heterogenous enhancement, bony destruction, and peritumoral edema should arouse suspicion.15 Song and colleagues9 note that TBM may be identified on imaging when all 3 of the following findings are present: low-signal intensity in the T1-weighted image, low or isosignal intensity in the T2-weighted image, and contrast enhancement in the gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image.

Although long considered a rarity, TBM appears to be more common than initially presumed. Several factors have been identified that likely contribute to TBM being underreported or entirely overlooked. First is that TBM is asymptomatic in nearly 40% of cases.6,16 Streitmann and Sismanis10 comment that TBM frequently occurs late in a malignancy’s course and may, therefore, be obscured by other earlier-appearing and more prominent metastatic foci. In addition, TBM may be overlooked when one considers that the temporal bone is typically not examined at autopsy, and metastatic evaluation often fails to include imaging of the temporal bones. On a positive note, metastatic spread to the temporal bone is becoming more readily recognized, as survival rates increase and the capabilities of diagnostic imaging continue to advance.14,17

Conclusion

SSNHL is one of several otologic disorders that may signal the presence of TBM. Often underreported or entirely overlooked, TBM is likely more common than initially thought. Patients with a history or current diagnosis of malignancy who present with a sudden onset of hearing loss, facial weakness, or other otologic reports must be evaluated for the presence of temporal bone metastasis.

1. Chandrasekhar SS, Tsai Do BS, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161 (suppl 1):S1-S45. doi:10.1177/0194599819859883

2. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). NIDCD fact sheet | hearing and balance: sudden deafness. NIH publication 00-4757. March 2018. Accessed May 3, 2022. www.nidcd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/health/hearing/Sudden-Deafness.pdf

3. O’Malley MR, Haynes DS. Sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2008;41(3):633-649. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2008.01.009

4. Kuhn M, Herman-Ackah SE, Shaikh JA, Roehm PC. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a review of diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Trends Amplif. 2011;15(3):91-105. doi:10.1177/1084713811408349

5. Chau JK, Lin JR, Atashband S, Irvine RA, Westerberg BD. Systematic review of the evidence for the etiology of adult sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(5):1011-1021. doi:10.1002/lary.20873

6. Gloria-Cruz TI, Schachern PA, Paparella MM, Adams GL, Fulton SE. Metastases to temporal bones from primary nonsystemic malignant neoplasms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(2):209-214. doi:10.1001/archotol.126.2.209

7. Dazert S, Aletsee C, Brors D, et al. Rare tumors of the internal auditory canal. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(7):550-554. doi:10.1007/s00405-003-0734-4

8. Jones AJ, Tucker BJ, Novinger LJ, Galer CE, Nelson RF. Metastatic disease of the temporal bone: a contemporary review. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):1101-1109. doi:10.1002/lary.29096

9. Song K, Park KW, Heo JH, Song IC, Park YH, Choi JW. Clinical characteristics of temporal bone metastases. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;12(1):27-32. doi:10.21053/ceo.2018.00171.

10. Streitmann, MJ Sismanis A. Metastatic carcinoma of the temporal bone. Am J Otol. 1996;17(5):780-783. https://journals.lww.com/otology-neurotology/Abstract/1996/09000/Metastatic_Carcinoma_of_the_Temporal_Bone.16.aspx

11. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492

12. Snyder MC, Heywood BM. Acute bilateral sensorineural hearing loss as the presenting symptom of metastatic lung cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(5):592-594. doi:10.1067/mhn.2001.115057

13. Brown, IS. Pathology of perineural spread. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2016;77(2):124-130. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1571837

14. Stucker FJ, Holmes WF. Metastatic disease of the temporal bone. Laryngoscope. 1976;86(8): 1136-1140. doi:10.1288/00005537-197608000-00005

15. Eliezer M, Tran H, Inagaki A et al. Clinical and radiological characteristics of malignant tumors located to the cerebellopontine angle and/or internal acoustic meatus. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40(9):1237-1245. doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000002360

16. Faucett EA, Richins H, Khan R, Jacob A. Metastatic prostate cancer to the left temporal bone: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2015:2015:250312. doi:10.1155/2015/250312

17. Morton AL, Butler SA, Khan A, Johnson A, Middleton P. Temporal bone metastases-pathophysiology and imaging. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97(6):583-587. doi:10.1177/2F019459988709700612