Peer Reviewed

From Routine to Rare: Splenic Injury Following Colonoscopy

A 75-year-old man developed sharp left upper quadrant pain immediately following an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy performed for persistent generalized abdominal discomfort.

History. The patient has a history of arrhythmia and is currently being treated for prostate cancer. He had been having vague abdominal discomfort for several weeks, which prompted further evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract with EGD and colonoscopy. Immediately after the procedure, he developed the severe sharp left upper quadrant abdominal pain that was worsened by movement and palpation. He also had nausea but no emesis. Repeat blood pressure was 79/44 mm Hg. On examination, the abdomen was distended and peritonitic with pronounced tenderness in the left upper quadrant.

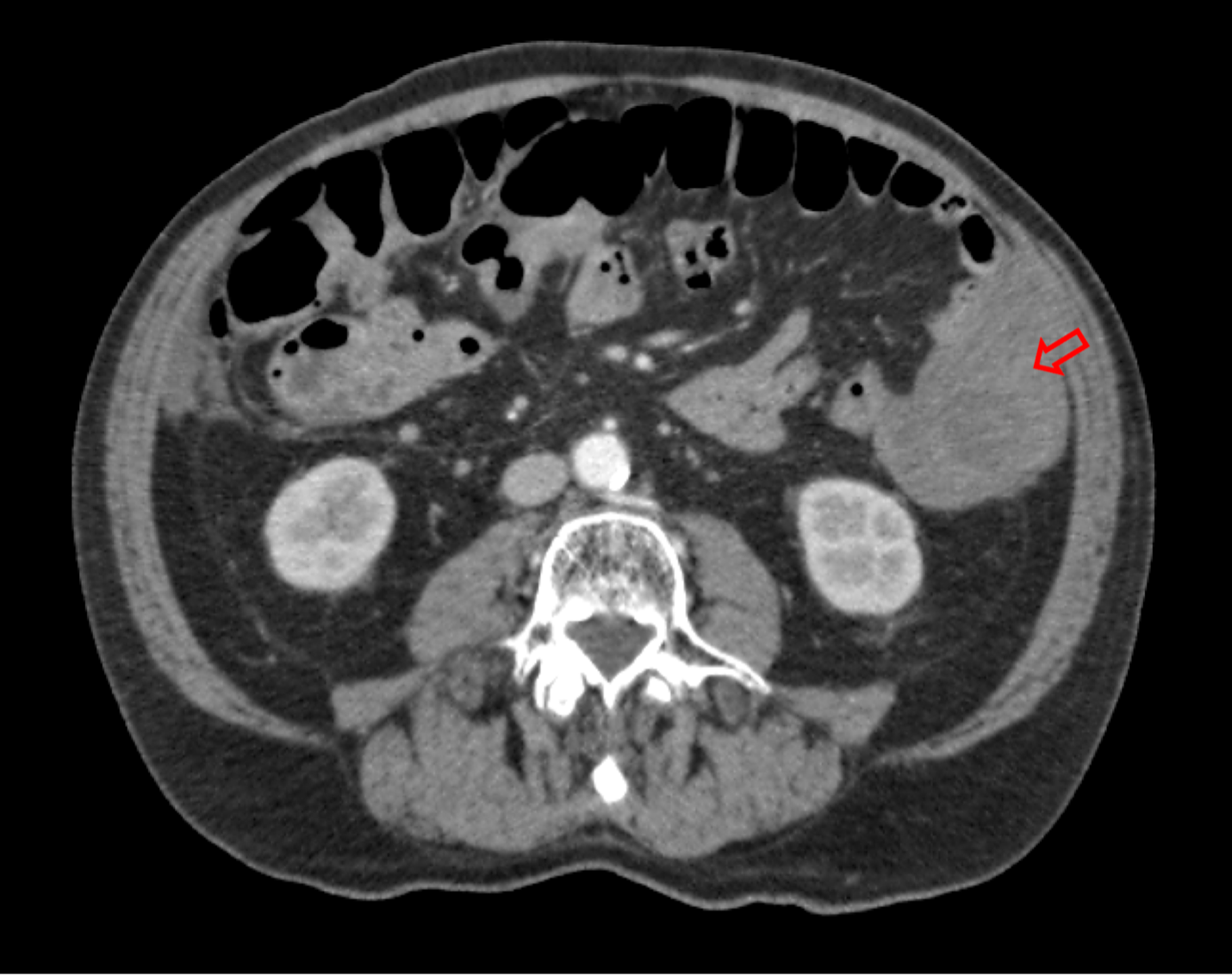

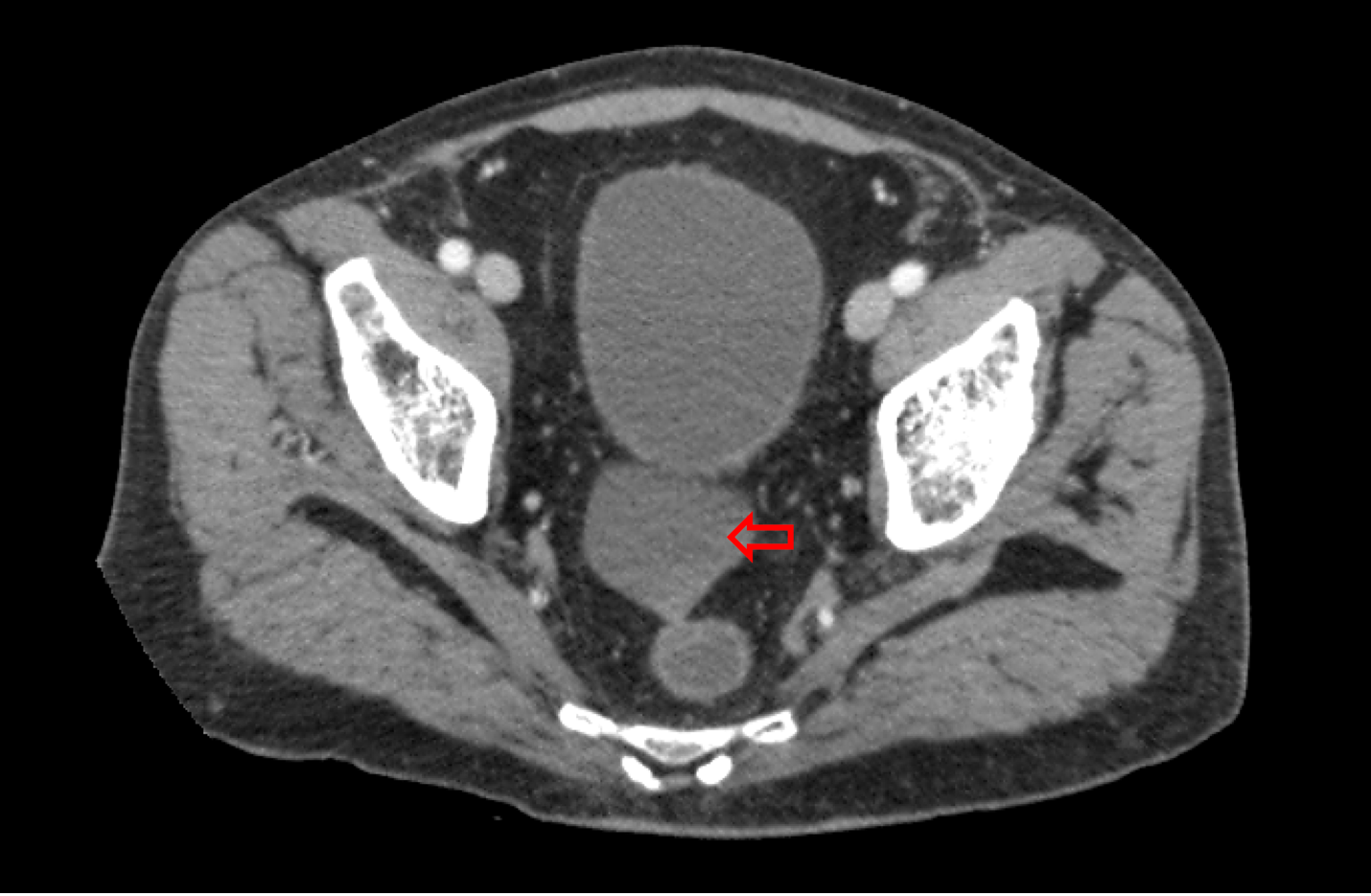

Diagnostic testing. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast was immediately obtained, which demonstrated a Grade 1 splenic laceration at the inferior pole with surrounding hemoperitoneum (Figure 1). There was an estimated one liter of blood collecting throughout the peritoneal cavity including around the liver, bowel, left paracolic gutter, and extending down into the rectovesical pouch (Figures 2 and 3). Subsequent laboratory work-up revealed that his hemoglobin and hematocrit declined to 8.0 g/dL and 24.4%, respectively (from previous 10.5 g/dL and 32.2%, prior to the procedure). His white blood cell count was within normal limits at 4.4 x 103/uL. Based on these results, the diagnosis of a Grade 1 splenic laceration secondary to colonoscopy was made.

Figure 1. Grade 1 splenic laceration with surrounding hematoma (solid arrow). Hemoperitoneum is visualized with blood surrounding the liver, bowel, and spleen (hollow arrows).

Figure 2. Blood tracking down the left paracolic gutter (hollow arrow).

Figure 3. Blood in the rectovesical pouch (hollow arrow).

Differential diagnoses. This patient’s hemodynamic instability and pain after a procedure indicated an acute and likely iatrogenic cause. Another more common complication of routine colonoscopy which could have caused similar symptoms is bowel perforation. However, this would present more commonly with fever, leukocytosis, and free air on imaging, none of which were present in this patient. Another possibility is a reaction to a sedative or other medications administered during the procedure, but the imaging confirmed a mechanical cause.

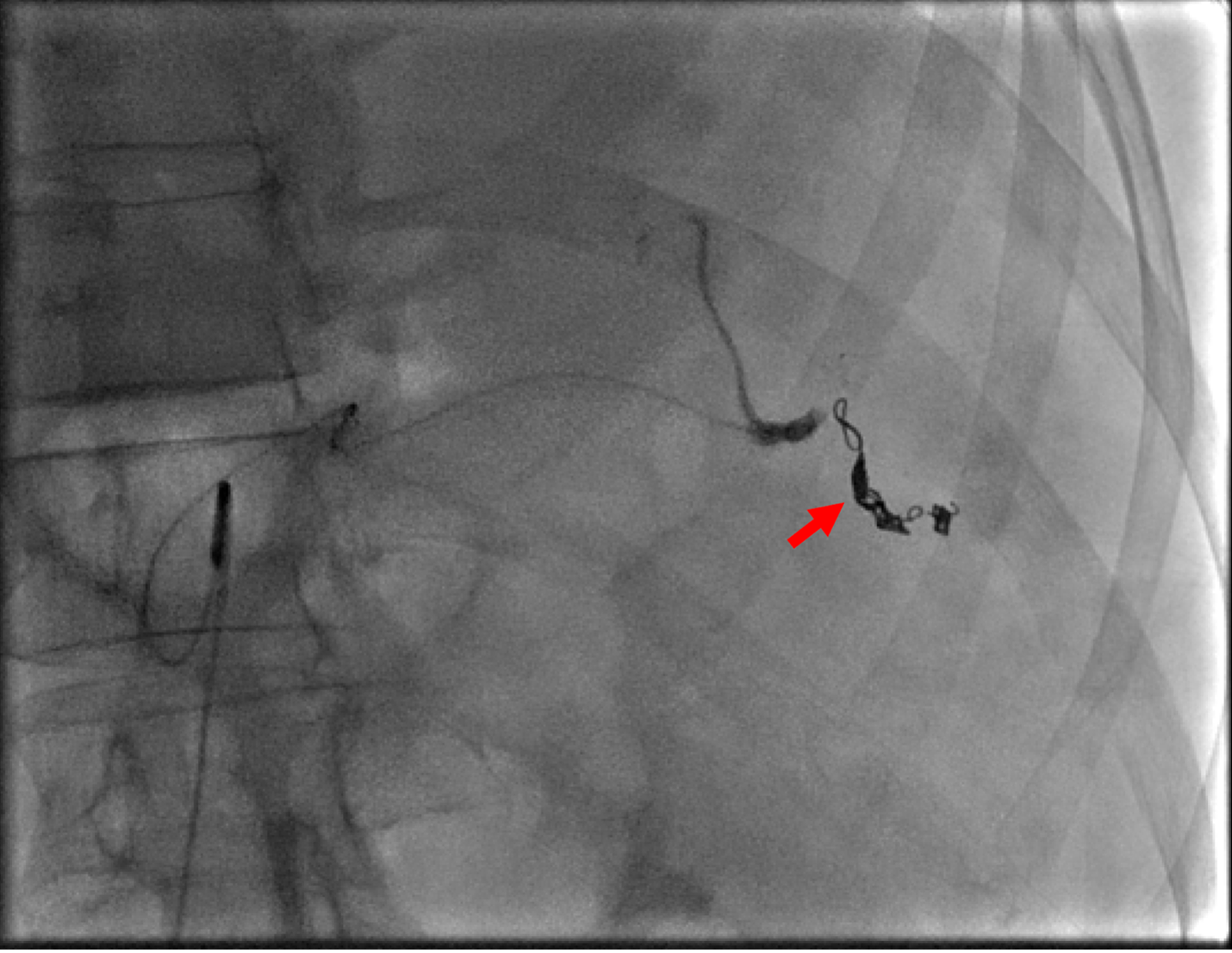

Treatment and management. The patient was stabilized with intravenous fluids and albumin and did not require a blood transfusion. Upon confirming bleeding from the spleen, an angiogram was immediately performed which identified a 7 mm pseudoaneurysm in the spleen's lower pole with active bleeding (Figure 4). Using ultrasound-guided access through the right common femoral artery, the catheter was directed to the splenic artery. The angiography pinpointed a descending branch feeding the pseudoaneurysm. Embolization of the descending branch was performed using gelatin sponge followed by fibered coils, both of which were visible in a post-procedure fluoroscopy (Figure 5). A microvascular plug was positioned proximally in the branch. Subsequent angiography confirmed the occluded arterial branch, absence of pseudoaneurysm filling, and cessation of bleeding (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Angiography of the distal splenic artery revealing a pseudoaneurysm in the lower pole of the spleen (solid arrow).

Figure 5. Post-embolization angiography with visualization of coil, microvascular plug, and gelatin sponge placed intra-arterially (solid arrow).

Figure 6. Post-embolization angiography demonstrating occlusion of a descending branch of the splenic artery (solid arrow), no active bleeding, and no residual filling of the pseudoaneurysm.

Outcome and follow-up. The patient's abdominal discomfort was managed with acetaminophen. His hemoglobin levels increased, and gastrointestinal symptoms resolved, permitting normal dietary resumption within a day. A follow-up CT scan 3 days later showed expected post-embolic splenic changes, including an anterior-inferior pole infarct, with no ongoing bleeding (Figure 7). Unfortunately, the patient developed aspiration pneumonia on post-operation day 4, potentially related to general anesthesia during the intervention. He was treated with intravenous antibiotics for 2 days and rapidly improved. He was subsequently discharged in stable condition and had an uneventful outpatient follow-up, without any significant post-procedure complications.

Figure 7. Post-embolic infarction of the inferior splenic parenchyma (solid arrow).

Discussion. Colonoscopy is a standard procedure for evaluating colorectal disease. Its most frequent complications are bowel perforation and bleeding, occurring in 0.4% to 2.5% of cases.1 A rarer yet significant complication is splenic injury, with an incidence of 0.00005-0.017%.2 Its rarity often results in diagnostic delays, potentially contributing to its mortality rate of 5%.2,3 Studies have suggested that risk factors for splenic injury include female sex, older age, prior abdominal surgery, anti-coagulant use, less experienced endoscopists, and concurrent polypectomy or biopsy.1,4,5

The spleen is the most frequently injured organ in blunt abdominal trauma. In clinical practice, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) splenic injury scale is commonly used for grading the severity of splenic injuries. This grading, ranging from Grade I to V, is based on the extent of laceration, the size of the hematoma, and the percentage of splenic involvement.6 In this case, the patient presented with a Grade I splenic laceration, which indicates a minor injury with minimal parenchymal disruption. However, this was complicated by the presence of a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm (SAP).

Splenic injuries manifest in various forms, including lacerations, ruptures, and SAP hemorrhages. During a colonoscopy, traction on the splenocolic ligament or external pressure mimicking blunt trauma can cause splenic lacerations.2 SAP often arises following conditions like pancreatitis or trauma, where degradation of the arterial intima and elastic lamina can occur. This degradation predisposes the vessel to pseudoaneurysm development.7

Most splenic injury symptoms emerge within 48 hours post-colonoscopy, with left upper quadrant abdominal pain being the predominant symptom.8,9 Specifically, patients with these injuries might report hematemesis, flank pain, and melena.10,11 Other nonspecific signs include dizziness, syncope, anemia, and hypotension.

Splenic injury diagnosis primarily employs CT with intravenous contrast, which has over 96% sensitivity and specificity.12 Radiological markers include hemoperitoneum, laceration, and subcapsular hematoma.13 While CT efficiently detects splenic laceration, additional imaging like visceral angiography and CT angiography may provide additional insight, such as detecting the presence of an SAP, further guiding therapeutic decisions.10

Embolization is a standard component of non-operative management for splenic injuries, particularly in hemodynamically stable patients.14 The technique involves inserting a catheter into the artery feeding the injured region, followed by the introduction of agents to occlude the blood flow and control bleeding. The choice between proximal and distal embolization depends on the location and nature of the injury. Proximal embolization aims to reduce the perfusion pressure and overall blood flow to the spleen, which can be beneficial in cases of diffuse injury without a localized bleeding point. Additionally, proximal embolization can be used when the source of bleeding, such as an SAP, is in a location difficult to access for distal embolization. Its advantage is also in its technical ease and rapidity. Splenic function is preserved to some degree by continued blood flow through collateral arteries such as the short gastric and left gastroepiploic arteries.14

In contrast, distal embolization is more targeted, focusing on the specific injured vessel or pseudoaneurysm.15 Endovascular interventions like coils, glue, or gelatin sponge are favored for hemodynamically stable patients.16 Following resuscitation, our patient was hemodynamically stable, and a descending branch feeding the pseudoaneurysm was identified and targeted for embolization.

For the gastroenterologist, the possibility of splenic injury represents a challenge. Its extreme rarity and certain poorly understood risk factors limit the endoscopist's options for definitive prevention. However, it's been suggested that awareness of specific endoscopic maneuvers that may raise injury risk can be helpful in preventing such injury. Slide-by advancement, alpha maneuvers, hooking the flexure, and straightening the sigmoid loop can increase stress on the splenocolic ligament, potentially raising the risk of injury.1,3 Similarly, looping of the endoscope near the splenic flexure may contribute to the risk of injury.3 While looping is common, recent technological developments aimed at reducing looping frequency17 and improving scope guidance18 may indirectly lessen the risk of this complication. Additionally, patient positioning has been explored, with the left lateral decubitus position suggested as potentially reducing spleen displacement during the procedure.1,3,19,20

While iatrogenic injuries may cause SAPs, it’s important to keep a broad differential diagnosis in mind. Chronic pancreatitis, due to its inflammatory nature, can lead to the formation of SAP.21 Another potential cause is segmental arterial mediolysis, a non-atherosclerotic, non-inflammatory vascular disorder.22 Necrotizing pancreatitis may cause extraparenchymal SAPs along the course of the splenic artery outside the spleen and often require embolization across the entire abnormal segment of artery.23

Conclusion. SAP post-colonoscopy, while rare, demands increased awareness as illustrated by our patient's presentation. Adopting preventative techniques, such as refined scope manipulation, could mitigate splenic injury risk. Comprehensive research is essential to pinpoint the exact risk factors and consequent outcomes.

- Piccolo G, Di Vita M, Cavallaro A, et al. Presentation and management of splenic injury after colonoscopy: a systematic review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24(2):95-102. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182a83493

- Ha JF, Minchin D. Splenic injury in colonoscopy: a review. Int J Surg. 2009;7(5):424-427. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.07.010

- Singla S, Keller D, Thirunavukarasu P, et al. Splenic injury during colonoscopy--a complication that warrants urgent attention. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(6):1225-1234. doi:10.1007/s11605-012-1871-0

- Amory R, Nijs Y. Hemoperitoneum after routine colonoscopy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;105:108044. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.108044

- Ullah W, Rashid MU, Mehmood A, et al. Splenic injuries secondary to colonoscopy: rare but serious complication. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;12(2):55-67. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v12.i2.55

- Kozar RA, Crandall M, Shanmuganathan K, et al. Organ injury scaling 2018 update: spleen, liver, and kidney. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(6):1119-1122. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002058

- Tessier DJ, Stone WM, Fowl RJ, et al. Clinical features and management of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm: case series and cumulative review of literature. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(5):969-974. doi:10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00710-9

- Zhang AN, Sherigar JM, Guss D, Mohanty SR. A delayed presentation of splenic laceration and hemoperitoneum following an elective colonoscopy: a rare complication with uncertain risk factors. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2018;6:2050313x18791069. doi:10.1177/2050313X18791069

- Enofe I, Burch J, Yam J, Rai M. Iatrogenic severe splenic injury after colonoscopy. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2020;2020:8824720. doi:10.1155/2020/8824720

- Chia C, Pandya GJ, Kamalesh A, Shelat VG. Splenic artery pseudoaneurysm masquerading as a pancreatic cyst-a diagnostic challenge. Int Surg. 2015;100(6):1069-1071. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00149.1

- Lalor PF, Mann BD. Splenic rupture after colonoscopy. JSLS. 2007;11(1):151-156.

- Saad A, Rex DK. Colonoscopy-induced splenic injury: report of 3 cases and literature review. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(4):892-898. doi:10.1007/s10620-007-9963-5

- Federle MP, Griffiths B, Minagi H, Jeffrey RB. Splenic trauma: evaluation with CT. Radiology. 1987;162(1):69-71. doi:10.1148/radiology.162.1.3786787

- Imbrogno BF, Ray CE. Splenic artery embolization in blunt trauma. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2012;29(2):147–149. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1312577

- Patil MS, Goodin SZ, Findeiss LK. Update: splenic artery embolization in blunt abdominal trauma. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2020;37(1):97-102. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3401845.

- Lim HJ. A review of management options for splenic artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;59:48-52. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2020.08.048

- Bruce M, Choi J. Detection of endoscopic looping during colonoscopy procedure by using embedded bending sensors. Med Devices (Auckl). 2018; 171-191. doi:10.2147/MDER.S146934

- Peter S, Reddy NB, Naseemuddin M, Zaibaq JN, McGwin G, Wilcox CM. Outcomes of use of electromagnetic guidance with responsive insertion technology (RIT) during colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7(02):E225-E231. doi:10.1055/a-0754-1879

- Skipworth JRA, Raptis DA, Rawal JS, et al. Splenic injury following colonoscopy–an underdiagnosed, but soon to increase, phenomenon? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(4):W6-W11. doi:10.1308/147870809X400994.

- Tse CC, Chung KM, Hwang JS. Prevention of splenic injury during colonoscopy by positioning of the patient. Endoscopy. 1998;30(6):S74-S75. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001358

- Dhali A, Ray S, Sarkar A, et al. Peripancreatic arterial pseudoaneurysm in the background of chronic pancreatitis: clinical profile, management, and outcome. Updates Surg. 2022;74(4):1367-1373. doi:10.1007/s13304-021-01208-y

- Cheng EM, Chen KL, Sharma V, et al. Rapid formation and rupture of multiple abdominal pseudoaneurysms: a life threatening case of segmental arterial mediolysis. Ann Vasc Dis. 2021;14(3):256-259. doi:10.3400/avd.cr.20-00172

- Borzelli A, Amodio F, Pane F, Coppola M, Silvestre M, Serafino MD, et al. Successful endovascular embolization of a giant splenic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to a huge pancreatic pseudocyst with concomitant spleen invasion. Pol J Radiol. 2021;86:e489-e95.

AFFILIATIONS:

1University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL

2Department of Radiology, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL

CITATION:

From routine to rare: splenic injury following colonoscopy. Consultant. Published online June 10, 2024. doi:10.25270/con.2024.06.000001

Received October 10, 2023. Accepted February 23, 2024.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

None.

CORRESPONDENCE:

George McCann, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Road, Gainesville, FL 32610 (umccann@ufl.edu)