Massive Splenic Cyst Infected with Salmonella Saintpaul

A previously healthy 18-year-old white male presented to the emergency room with complaint of sharp left upper quadrant pain—exacerbated with deep inspiration—that had been gradually worsening over the past 2 days.

History

The patient had noted subjective fevers and chills at home, but had not taken his temperature. He denied participation in organized sports or any antecedent trauma. There was no associated nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. His past medical history was notable for irritable bowel syndrome and scoliosis, for which he had a corrective surgery. The patient denied smoking, drugs, and alcohol. His religious preference was Jehovah’s Witness.

He was up-to-date on his immunizations and did not recently ingest any outpatient medications. There were no recent illnesses noted in the patient’s immediate family. He recently vacationed with his family to an amusement park in Florida.

Physical Examination

Physical exam in the emergency department revealed an uncomfortable and ill-appearing patient. His vital signs included a temperature of 96.4°F, blood pressure of 116/64 mm Hg, a pulse of 86 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, pain at a 3/10, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air.

Upon inspection of his abdomen, there was diffuse tenderness with fullness noted in the left upper quadrant. However, a discrete mass could not be palpated. The remainder of his examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 40,000/µL (with a differential of 89.7% neutrophils, 5.5% lymphocytes, 4.8% monocytes, 0% esonophils, and 19% bands), a hemoglobin of 14.8 g/dL, and a platelet count of 156,000. The basic metabolic profile was notable only for a sodium of 134 mmol/L, BUN of 23 mg/dL, and creatinine of 1.24 mg/dL.

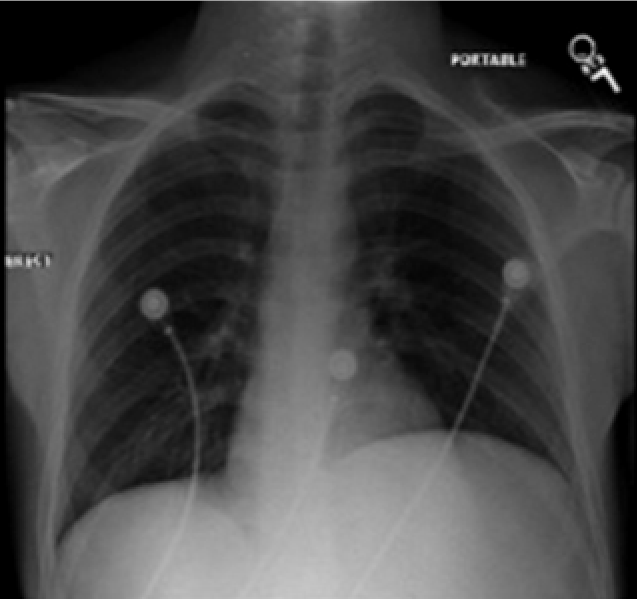

Figure 1. Chest x-ray showing an elevated left hemidiaphragm.

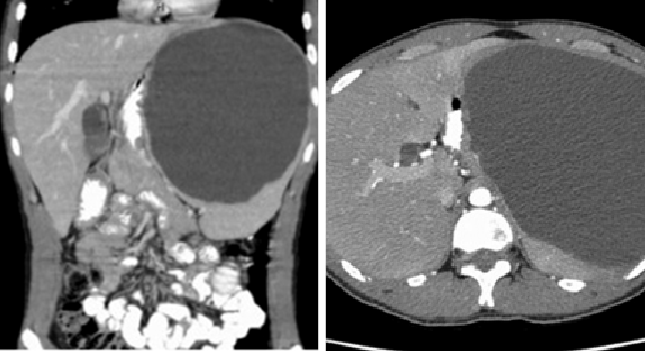

The chest x-ray showed only an elevated left hemidiaphragm (Figure 1). A CT of the abdomen with IV and PO contrast (Figures 2 and 3) showed a large (16 cm at its greatest dimension) nonsolid cystic mass within the spleen having a significant mass effect on the kidney, aorta, and stomach. The fluid measured 15 Hounsfield units (a much lower density than would be expected from blood)—suggesting a slightly proteinaceous source.

Figures 2 and 3. CT scan showing a large splenic cyst.

Treatment

Due to the elevated white blood cell count and the patient’s subjective complaints of fever, an infected splenic cyst was suspected and the patient was admitted to the general medical ward with consultation to an infectious disease specialist for antibiotic management. In order to minimize the risk of blood loss and preserve splenic function, a percutaneous drainage of the splenic cyst fluid was performed via interventional radiology on hospital day 4 with drainage of approximately 2200 cc of brown, cloudy fluid with a pigtail catheter left in place.

A pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccine was administered on hospital day 6. Culture of the aspirated fluid showed Salmonella serotype Saintpaul that was sensitive to ciprofloxacin. A possible cardiac source for the infected cyst was ruled out after a normal transthoracic echocardiogram and blood cultures were negative for any bacterial growth.

After 9 days of hospital stay, the patient was discharged home with the pigtail percutaneous catheter and ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice a day for 2 weeks of outpatient therapy.

The patient was seen 6 days later in the emergency department after he accidentally pulled the percutaneous catheter. A repeat CT scan done at the time showed an interval improvement of the splenic fluid collection (Figure 4). The drainage catheter was noted to be outside the spleen and was subsequently removed by interventional radiology. A follow-up CT scan 1 week later revealed that the overall appearance of the spleen had not changed significantly from the prior study (Figure 5).

Figure 4. CT scan showing the drainage catheter outside the splenic fluid

Figure 5. The spleen showing residual fluid collection 22 days post drainage.

Discussion

First described in 1829, splenic cysts are uncommon with only 800 cases referenced in literature.1 Splenic cysts are categorized as either primary or secondary according to the epithelium that lines their inner surface. Primary cysts are further divided into either parasitic or nonparasitic.2 While the nonparasitic type is mostly seen in children and young adults, parasitic cysts (uncommon in Europe and North America) are the most common type of splenic cysts in the world.2-4

Females have a higher reported incidence of splenic cysts than men, with the largest age group noted to be women in their 20s.5,6 The majority of splenic cysts are asymptomatic, manifesting at times due to mass effect, or incidentally found during routine imaging studies.7 Cysts with diameters measuring >5 cm are at risk for rupture resulting in life-threatening complications, such as hemorrhage and peritonitis.1,5

Surgery

Image guided percutaneous drainage have been reported to have a cystic recurrence rate as high as 100%.5 For this reason, splenectomies have been the surgical approach of choice for splenic cysts this size and those that are secondarily infected, with the aim of cyst eradication and prevention of fluid re-accumulation.5,8

While a splenectomy offers a chance to examine the removed spleen for histopathological review and classification, new understanding of the spleen’s role on immune function has shifted surgical practice towards emphasis on minimally invasive techniques and spleen preservation.2 The goal of splenic preservation is to avoid post-splenectomy overwhelming sepsis, which has the greatest risk during the first 2 years post-splenectomy..8 The procedure also carries a mortality rate of about 40% to 70%.5,8 Laparoscopic splenic fenestration, entailing cyst removal, and preservation of splenic function has been described in the literature recently as a successful surgical alternative to full splenectomies.5

Salmonella Saintpaul

Saintpaul is a very rare Salmonella serotype—ranked 14 among the 15 most common serotypes and representing 5530 out of 441,863 cases—that has been linked mostly to food outbreaks with the main symptoms being diarrhea, abdominal cramps, fever, and headaches.9,10 Diarrheal illness in humans caused by salmonellosis is important as it leads to approximately 1.4 million illnesses and 600 deaths annually in the United States.10 Most salmonella infections occur as sporadic infections rather than recognized outbreaks.9 Recent Salmonella Saintpaul food outbreaks were linked to jalapeño peppers in 2008, alfalfa sprouts in 2009, and cucumbers in 2013.11,12 From 1996-2006, Salmonella Saintpaul serotype was responsible for 17.7% hospitalizations, 4.1% invasive diseases, and no deaths.13

Antimicrobial therapy may be life saving for patients with extra intestinal infection.14 Jones et al found that the overall proportion of persons hospitalized was higher for those with salmonella isolates from invasive sites than those with stool isolates.13

Outcome of the Case

Our patient was infected by Salmonella Saintpaul. Even though his splenic cyst was very large, his management prompted a more conservative percutaneous approach (with a lower risk of bleeding leading to possible transfusions) given his status as Jehovah’s Witness.

We considered the possibility that the patient had a prior Salmonella gastrointestinal infection, which led to the infected splenic cyst. His intermittent diarrheal symptoms were not a new complaint secondary to his coincident history of irritable bowel syndrome. Additionally, the patient’s family members were not ill during or after the travel to Florida and stool samples were not sent for culture during our patient’s hospitalization.

He was empirically started on ampicillin/sulbactam and was given a single dose of amikacin when his temperature remained persistently elevated. Once identification and sensitivities were reported, he was narrowed to ciprofloxacin and discharged on the same medication.

During subsequent follow-up visits with the infectious diseases service, the patient denied any further symptoms. A complete blood count performed at follow-up was within normal limits.

Infected massive splenic cysts are rare with extra intestinal Salmonella Saintpaul serotype infections scarcely reported. Antibiotic therapy and surgical techniques, with the aim of cystic removal or drainage while preserving splenic function, are the goals of management. ■

Alan Lucerna, DO, is an associate program director of emergency medicine residency at Rowan School of Osteopathic Medicine and an attending physician at Kennedy University Hospital in Stratford, NJ.

Tameka Simpson, DO, is an infectious disease physician at Southeastern Center for Infectious Disease in Tallahassee, FL. She also serves as a clinical associate professor at Florida State University College of Medicine.

Ramneet Wadehra, DO, is a cardiology fellow at the Rowan School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, NJ.

Jamey Hourigan, DO, is currently a 4th year emergency medicine resident at Rowan School of Osteopathic Medicine.

References:

1.Balzan SM, Riedner CE, Santos LM, et al. Posttraumatic splenic cysts and partial splenectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31:262–265.

2. Hansen MB, Moller AC. Splenic cysts. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2004;14:316-322.

3. Mirilas P, Mentessidou A, Skandalakis JE. Splenic cysts: are there so many types? J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:459-465.

4. Morgenstern L. Nonparasitic splenic cysts: pathogenesis, classification, and treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194(3):306-314.

5. Geraghty M, Khan IZ, Conlon KC. Large primary splenic cyst: A laparoscopic technique. J Min Access Surg. 2009;5:14-16.

6. Ito Y, Shimizu E, Miyamoto T, et al. Epidermoid cysts of the spleen occurring in sisters. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(3):619-623.

7. Wu HM, Kortbeek JB. Management of splenic pseudocysts following trauma: a retrospective case series. Am J Surg. 2006;191(5):631-634.

8. Morris G, Foster M. Chicken fancier’s spleen. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52(4):272-273.

9. Olsen SJ, Bishop R, Brenner F, et al. The changing epidemiology of salmonella: trends in serotypes from humans in the United States, 1987-1997. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:753-761.

10. Jain S, Bidol SA, Austin JL, et al. Multistate outbreak of Salmonella Typhimurium and Saintpaul infections associated with unpasteurized orange juice—United States, 2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(8):1065-1071.

11. CDC. Investigation outbreak of infections caused by Salmonella Saintpaul. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/saintpaul/. Accessed March 2014.

12. CDC. Multistate outbreak of Salmonella Saintpaul infections linked to imported cucumbers. 2013 Jun 20. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/saintpaul-04-13/map.html. Accessed March 2014.

13. Jones TF, Ingram LA, Cieslak PR, et al. Salmonellosis outcomes differ substatnially by serotype. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:

109-114.

14. Varma JK, Molbak K, Barrett TJ, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella is associated with excess bloodstream infections and hospitalizations. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(4):554-561.