A Long-Swollen Lip, Then Daily Fever and Vomiting: What’s the Cause?

A 3½-year-old boy presented with a chief concern of episodes of daily high fevers and vomiting.

The child’s recent medical history was notable for painless extensive swelling of the left half of his upper lip a month before his third birthday (Figure 1). The parents reported that the swelling had developed suddenly during a walk outside; the immediate and extensive localized swelling led them to assume initially that he had been stung or bitten by an insect, despite that he did not react as if in pain.

The swelling, which was associated with no other symptoms, persisted for approximately 8 months. During this time, the boy had been seen by his primary care physician, 2 dentists, an oral surgeon, an endodontist, a rheumatologist, an otorhinolaryngologist, an infectious disease specialist, a dermatologist, and a plastic surgeon, but he had not received a definitive diagnosis. The child’s parents had opted against biopsy of the lesion.

On presentation, the swelling had resolved to the point at which the lip had nearly returned to its baseline size. Recently, the boy developed fever and abdominal pain that initially had been attributed to acute infectious gastroenteritis. But these episodes of fever and pain reoccurred and became more frequent and intense, ultimately becoming a pattern of daily fevers as high as 40.5°C, vomiting, and a low energy level.

History

The boy had been born at term to a 25-year-old woman, gravida 3, para 3, by way of uncomplicated, normal, spontaneous vaginal delivery. Birth weight was 4.68 kg. The child had been breastfed.

The boy’s family history is positive for Graves disease in his maternal grandfather, colon cancer in his paternal grandfather, Crohn disease in his father, migraine in his mother and maternal grandmother, and atopy in numerous relatives in both parents’ families.

The child’s past medical history is positive for eczema and a left radial buckle fracture after a fall 5 months ago at 30 months of age. He is allergic to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

He lives with his mother, his father, and 4 siblings. The family has no pets, and they have recently traveled to Israel.

What is the cause of the boy’s swollen lip? And what explains his fever and abdominal pain?

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: Crohn disease presenting with cheilitis granulomatosa

A complete blood count was ordered, the results of which included a white blood cell count of 8,600/µL, a hematocrit of 28%, a hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL, and a platelet count of 779 × 103/µL. Serum iron was 11 µg/dL, with a total iron binding capacity of 263 µg/dL and a transferrin saturation of 4%. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 64 mm/h, and C-reactive protein level was 1.8 mg/L.

Results of complement studies, immunodeficiency profile, and thyroid function tests were normal. The results of a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal, except for an albumin level of 2.3 g/dL. Results of Prometheus IBD serology 7 testing for inflammatory bowel disease did not indicate the presence of Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. Results of tests for antinuclear antibodies, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Cultures were negative for acid-fast bacilli, Bartonella, and fungi.

An upper gastrointestinal series with small bowel follow-through, abdominal ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, and chest radiography were performed, the results of which were within normal limits. Bone marrow was normocellular on biopsy.

Results of endoscopy with biopsy and colonoscopy with biopsy were normal. Abdominal computed tomography results were, however, notable for diffuse inflammatory changes, fat stranding, mesenteric lymphadenopathy, and thickening of the small bowel wall.

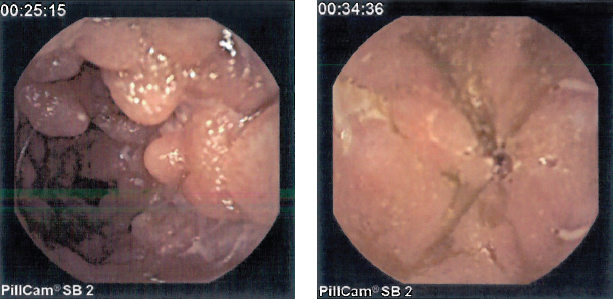

The boy underwent capsule endoscopy, in which a pill-camera was inserted into the digestive tract and photographed the proximal small intestine beyond the reach of the endoscope.

There, in the patient’s jejunum, photographic evidence of Crohn disease was visualized—specifically, pseudopolyps (Figure 2) and ulcers (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Capsule endoscopy images revealed pseudopolypoid manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in the jejunum.

Figure 3. Photographs of the wall of the small intestine showed jejunal ulcers, leading to a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Based on the presentation and the results of diagnostic tests and procedures, the boy received a diagnosis of Crohn disease (CD); his swollen lip was attributed to cheilitis granulomatosa, a rare presenting sign of CD. He was started on a regimen of prednisone, after which his fevers and vomiting subsided.

Discussion

CD is part of a larger diagnostic spectrum of autoimmune inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that also includes ulcerative colitis. CD causes transmural inflammation in any area of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus.

Presenting symptoms can include diarrhea, abdominal pain, blood in the stool, anal skin tags, anal fistulae, weight loss, and poor growth. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammation can be expressed in the eyes (uveitis), skin (erythema nodosum), joints (arthritis), nails (clubbing), and mouth (aphthous ulcers). More fulminant presentations include fatigue, anemia, fever, leukocytosis, grossly bloody stool, and hypoalbuminemia.

CD is most commonly diagnosed in patients between the ages of 15 and 25 years, with another, smaller incidence peak in the 40s and 50s. Fewer than 10% of patients receive a diagnosis before the age of 6 years.1

Cheilitis granulomatosa is a painless swelling of the lip or lips that occurs as a result of a growing collection of granulomas. Owing to its granulomatous nature, it has been associated with CD, which has a similar histopathology. Cheilitis granulomatosa is, however, a rare presenting sign of CD. Only 0.5% of patients with CD will ever develop cheilitis granulomatosa,2 but often the lip swelling—which arises abruptly and resolves spontaneously, as it did in this patient—precedes the IBD diagnosis.

The diagnosis of CD relies on clinical suspicion and the results of laboratory tests, imaging studies, and pathology tests. A positive family history supports the diagnosis, since the NOD2 gene and other genes have been implicated in the heritability of CD. Approximately 30% of children who receive a diagnosis of CD or other form of IBD can identify at least one close relative with IBD.3 Biopsies of the large intestine and small intestine also help confirm a diagnosis of IBD histologically.

References:

1. Gupta N, Bostrom AG, Kirschner BS, et al. Presentation and disease course in early- compared to later-onset pediatric Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(8):2092-2098.

2. Wiesen A, David O, Katz S. Cheilitis granulomatosa: Crohn’s disease of the lip? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(9):865-866.

3. Heyman MB, Kirschner BS, Gold BD, et al. Children with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): analysis of a pediatric IBD consortium registry. J Pediatr. 2005;146(1):35-40.

Dr Wilbur is a pediatrician at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio.