Peer Reviewed

An Atlas of Nail Disorders, Part 9

AUTHORS:

Alexander K. C. Leung, MD1,2 • Benjamin Barankin, MD3 • Kin Fon Leong, MD4 • Joseph M. Lam, MD5

AFFILIATIONS:

1Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

2Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

3Toronto Dermatology Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

4Pediatric Institute, Kuala Lumpur General Hospital, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

5Department of Pediatrics and Department of Dermatology and Skin Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

CITATION:

Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF, Lam JM. An atlas of nail disorders, part 9. Consultant. 2020;60(7):e10. doi:10.25270/con.2020.07.00002

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Alexander K. C. Leung, MD, #200, 233 16th Ave NW, Calgary, AB T2M 0H5, Canada (aleung@ucalgary.ca)

EDITOR’S NOTE:

This article is part 9 of a 15-part series of Photo Essays describing and differentiating conditions affecting the nails. Parts 10 through 15 will be published in upcoming issues of Consultant. To access previously published articles in the series, visit the Consultant archive at www.Consultant360.com and click the “Journals” tab.

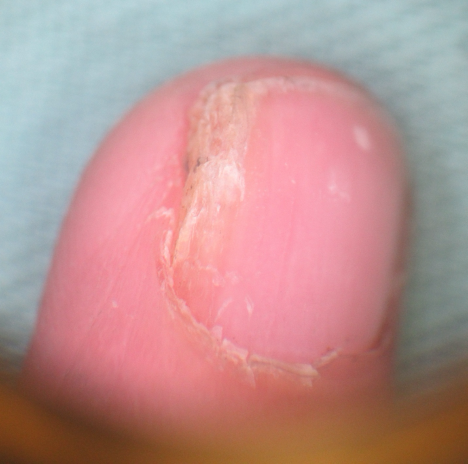

Half-and-Half Nails

Half-and-half nails, also known as Lindsay’s nails, were first described by William B. Bean, MD, in 1963 in two patients with kidney disease.1 The term half-and-half nail was coined by Philip G. Lindsay, MD, in 1967, and the condition now bears his name.2 Half-and-half nails are characterized by a proximal white, ground-glass–looking nail plate and a distal pink, red, or brown nail plate, with the latter occupying at least 20% to 60% of the total length of the nail (Figure 1).3,4 The two discolorations of the proximal and distal nail plates are well-defined, run parallel to the distal or free margin of the nail, and do not change under pressure.3,5 Also, the configuration does not change with the growth of the nails.3,5 The condition affects mainly fingernails, and less often, toenails.6

Figure 1. Half-and-half nails are characterized by a proximal white, ground-glass–looking nail plate and a distal pink, red, or brown nail plate, with the latter occupying at least 20% to 60% of the total length of the nail.

The proximal white band is believed to result from chronic anemia, increased thickness of the capillary wall, and overgrowth of connective tissue between the nail plate and the underlying structure with reduction of blood flow in the subpapillary plexus.5,7,8 The distal pink, red, or brown nail plate is caused by increased melanin deposition, possibly stimulated by uremic or other toxins or by stagnant venous return.3,4,7 Because the two bands do not move with growth of the nail, the nail bed is likely to be the primary pathologic site.3

Half-and-half nails occur in 8% to 50% of patients with chronic kidney failure, especially those on hemodialysis.5-7,9,10 There is, however, no correlation between the depth of the distal color band and the severity of azotemia.6 The condition may also occur in association with Crohn disease, Kawasaki disease, Behçet disease, yellow nail syndrome, liver cirrhosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, pellagra, citrullinemia, zinc deficiency, and use of medications (eg, isoniazid, chemotherapeutic agents).3-16 Half-and-half nails may also be idiopathic and occur in healthy individuals.5,10

Longitudinal half-and-half nails, a rare clinical variant, have also been described.13,17 The condition usually occurs on the thumbs and toes. Longitudinal half-and-half nails can be caused by chronic trauma to the digit or can be idiopathic.13

Half-and-half nails should be distinguished from Terry’s nails, in which the distal pink, red, or brown nail plate occupies less than 20% of the total length of the nail (Figure 2).5,13 Typically, Terry’s nails are characterized by ground-glass opacification of nearly the entire nail (greater than 80% of the entire surface) and obliteration of the lunula.18 Terry’s nails can be an indication of an underlying disease—notably, cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, and congestive heart failure.18 The condition can also result from aging, viral hepatitis, chronic allograft nephropathy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and tuberculoid leprosy.18

Figure 2. Half-and-half nails should be distinguished from Terry’s nails, in which the distal pink, red, or brown nail plate occupies less than 20% of the total length of the nail.

REFERENCES:

- Bean WB. Nail growth: a twenty-year study. Arch Intern Med. 1963;111(4):476‐482. doi:10.1001/archinte.1963.03620280076012

- Lindsay PG. The half-and-half nail. Arch Intern Med. 1967;119(6):583‐587. doi:10.1001/archinte.1967.00290240105007

- Afsar FS, Ozek G, Vergin C. Half-and-half nails in a pediatric patient after chemotherapy. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2015;34(4):350‐351. doi:10.3109/15569527.2014.999861

- Singh S, Silver MS, Gasiorek MA, Koratala A. Half and half nails. Am J Med. 2020;133(2):e54‐e55. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.042

- Oanță A, Iliescu V, Țărean S. Half and half nails in a healthy person. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25(4):303‐304.

- Huang W-T, Wu C-C. Half-and-half nail. CMAJ. 2009;180(6):687. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081312

- Ma Y, Xiang Z, Lin L, Zhang J, Wang H. Half-and-half nail in a case of isoniazid-induced pellagra. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31(5):329‐331. doi:10.5114/pdia.2014.40969

- Ruiz-Villaverde R, Sánchez-Cano D, Martinez-Lopez A, Tercedor-Sánchez J. Reply to: idiopathic ‘Half and half’ nails. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(12):e215‐e216. doi:10.1111/jdv.13547

- Gandhi K, Prasad D, Malhotra V, Agrawal D. Half-and-half nails. Indian J Nephrol. 2014;24(5):330. doi:10.4103/0971-4065.133038

- Verma P, Mahajan G. Idiopathic ‘half and half’ nails. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(7):1452. doi:10.1111/jdv.12507

- Çakmak SK, Gönül M, Aslan E, Gül U, Kiliç A, Heper AO. Half-and-half nail in a case of pellagra. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16(6):695‐696.

- Chadwick A, Thwaites V, Holland M, Shahidi M. Half-and-half nails in a patient on antituberculosis treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017219841. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219841

- Cohen PR. Longitudinal half-and-half nails: case report and review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(4):331‐334. doi:10.1159/000487860

- Gönül M, Hızlı P, Gül Ü. Half-and-half nail in Behçet’s disease. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(1):e26‐e27. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05471.x

- Pellegrino M, Taddeucci P, Mei S, Peccianti C, Fimiani M. Half-and-half nail in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(11):1366‐1367. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03660.x

- Zágoni T, Sipos F, Tarján Z, Péter Z. The half-and-half nail: a new sign of Crohn’s disease? Report of four cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(7):1071‐1073. doi:10.1007/s10350-006-0525-2

- Wollina U, Bula P. Longitudinal ‘half-and-half nails’ or true leukonychia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):185‐186. doi:10.1159/000444757

- Witkowska AB, Jasterzbski TJ, Schwartz RA. Terry’s nails: a sign of systemic disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62(3):309‐311. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_98_17

Onychomatricoma

Onychomatricoma is a rare, benign, subungual tumor of fibroepithelial cells in the nail matrix.1 The condition was first described in 1992 by Baran and Kint.2 The classic clinical signs are localized or diffuse thickening of the nail plate (pachyonychia), yellow longitudinal bands (longitudinal xanthonychia), prominent longitudinal ridging, increased transverse curvature of the nail plate, splinter hemorrhages, and woodworm-like, honeycomb-like, or sponge-like cavities at the distal margin of the nail plate (Figure 1).1,3-5

Figure 1. The classic clinical signs of onychomatricoma are pachyonychia, longitudinal xanthonychia, prominent longitudinal ridging, increased transverse curvature of the nail plate, splinter hemorrhages, and woodworm-like, honeycomb-like, or sponge-like cavities at the distal margin of the nail plate.

Onychomatricoma is typically painless and slow-growing.5 Other possible clinical manifestations include erythema and swelling at the proximal nail fold, pain during nail compression, subungual hematoma, melanonychia striata, erythronychia, plate fracture, nail dystrophy, and dorsal pterygium.3,5-7 Approximately two-thirds of cases occur in the fingers.3 The male to female ratio is approximately 2 to 3.2 The peak incidence is in the fifth decade of life.4,5,8 The condition is more common in white individuals.1,8,9

Dermoscopic findings include woodworm-like cavities at the distal nail plate, longitudinal parallel yellow, white, or gray bands, and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 2).1,6 Ultrasonography may show hypoechogenic areas under the proximal nail fold affecting the nail matrix, and hyperechogenic linear dots corresponding to the fingerlike projections deforming the plate.1,6,8 Magnetic resonance imaging may show a high uptake near the distal fingerlike projections and a low uptake near the nail matrix.1,6 Histologic examination of the distal clipping of the involved nail plate typically shows increased thickness of the nail plate, multiple cavitations filled with serous fluid, and multiple fingerlike projections arising from the nail matrix with “glove finger” digitations onto the nail plate lined with matrix epithelium.1,5

Figure 2. Dermoscopic findings of onychomatricoma include woodworm-like cavities at the distal nail plate, longitudinal parallel yellow, white, or gray bands, and splinter hemorrhages.

Onychomatricoma micropapilliferum, a variant of onychomatricoma, has recently been described.10 In onychomatricoma micropapilliferum, the free edge of nail plate is thickened but without discernible cavities.10 Histologically, onychomatricoma micropapilliferum is distinguished from the classic onychomatricoma by the lack of cavitations at the in the nail plate, a papillated epithelial hyperplasia pattern rather than a digitate pattern, and a special pattern of matrical keratinization with pseudohorn cysts.10

The treatment of choice is avulsion of the nail with surgical excision of the entire nail matrix proximal to the tumor in order to prevent recurrence of the tumor.5,8

REFERENCES:

- Behrens EL, Khan M, Sturgeon A, Tarbox M. Onychomatricoma in a patient with extensive vitiligo: answer. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41(2):159‐160. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000966

- Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma. Filamentous tufted tumour in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(5):510‐515. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb11827.x

- Di Chiacchio N, Tavares GT, Tosti A, et al. Onychomatricoma: epidemiological and clinical findings in a large series of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1305‐1307. doi:10.1111/bjd.13900

- Isales MC, Haugh AM, Bubley J, et al. Pigmented onychomatricoma: a rare mimic of subungual melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(5):623‐626. doi:10.1111/ced.13418

- Kamath P, Wu T, Villada G, Zaiac M, Elgart G, Tosti A. Onychomatricoma: a rare nail tumor with an unusual clinical presentation. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(3):171‐173. doi:10.1159/000484577

- Cinotti E, Veronesi G, Labeille B, et al. Imaging technique for the diagnosis of onychomatricoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(11):1874‐1878. doi:10.1111/jdv.15108

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, Sergi CM. Melanonychia striata: clarifying behind the Black Curtain. A review on clinical evaluation and management of the 21st century. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(11):1239‐1245. doi:10.1111/ijd.14464

- Prevezas C, Triantafyllopoulou I, Belyayeva H, et al. Giant onychomatricoma of the great toenail: case report and review focusing on less common variants. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):202‐208. doi:10.1159/000445386

- Beirão P, Pereira P, Nunes A, Barreiros H. An unusually large onychomatricoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016218574. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-218574

- Perrin C. Onychomatricoma micropapilliferum, a New variant of onychomatricoma: clinical, dermoscopical, and histological correlations (report of 4 cases). Am J Dermatopathol. 2020;42(2):103‐110. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001440