Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis

An 18-year-old boy with a long history of subjective fevers associated with recurrent right knee pain and swelling presented to our institution for a second opinion. At age 12 years, his symptoms were attributed to osteomyelitis of the right medial femoral condyle. Despite negative bone culture results, he received a 4-week antibiotic course. Right knee pain recurred 5 years later, and bone cultures were again negative for infection. The boy was treated with intravenous antibiotics for presumed osteomyelitis. He had no other significant medical history, specifically no other joint involvement and no history of trauma, recent travel, or preceding infection.

An 18-year-old boy with a long history of subjective fevers associated with recurrent right knee pain and swelling presented to our institution for a second opinion. At age 12 years, his symptoms were attributed to osteomyelitis of the right medial femoral condyle. Despite negative bone culture results, he received a 4-week antibiotic course. Right knee pain recurred 5 years later, and bone cultures were again negative for infection. The boy was treated with intravenous antibiotics for presumed osteomyelitis. He had no other significant medical history, specifically no other joint involvement and no history of trauma, recent travel, or preceding infection.

On examination, the healthy-appearing teenager had mild effusion of the right knee, with tenderness at the medial femoral condyle. There was no evidence of rash or acne, other joint pain, morning stiffness, or back pain. He denied abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, and weight loss.

A radiograph of the right knee showed periosteal reaction of the medial aspect of the distal femur and focal lucencies and sclerosis in the metaphysis (A). Radiographs of the left pelvis and knee showed enthesopathy with bony proliferation change on the left greater trochanter (B) and left medial tibial plateau (C).

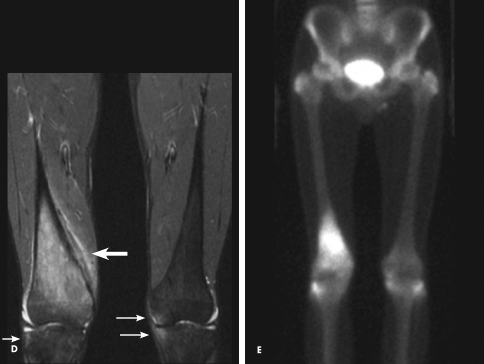

A coronal T2-weighted MRI scan showed bone marrow edema in the metaphysis of the right distal femur, periosteal reaction of the medial distal femur, and edema in the adjacent soft tissues (D, large arrow). There were also small areas of increased signal in the right and left lateral tibial and left medial tibial plateaus, as a result of enthesitis (D, small arrows).

A bone scan revealed high uptake in the metaphysis of the right distal femur and increased uptake in the right and left greater trochanters, right and left lateral and left medial tibial plateaus, and left medial femoral condyle (E).

The history and imaging findings are consistent with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO), an inflammatory bone condition characterized by bone pain, soft tissue swelling, and osteolysis that predominantly affects children. It may be accompanied by fevers. Elevated inflammatory markers are present in up to 65% of cases. Lesions usually involve the metaphyses of lower extremities, with a median number of 3.5 lesions per patient.1 It is not uncommon for CRMO to be misdiagnosed as an infectious osteomyelitis and treated as such despite negative culture results.

CRMO is classified under the umbrella term “chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis.” Similar bony lesions occur in SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis); however, dermatologic manifestations may be absent in childhood. Of

patients with CRMO, acne, psoriasis, synovitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or ankylosing spondylitis may develop in 20% to 30%.2 Enthesitis-related arthritis may develop in some patients years later.3

Histology of early lesions typically demonstrates inflammatory changes, increased osteoclasts, and bone resorption.4 Plain radiographs of early CRMO show osteolytic lesions with periosteal reaction. MRI is highly sensitive for detecting active CRMO lesions in bone.2

Histology of early lesions typically demonstrates inflammatory changes, increased osteoclasts, and bone resorption.4 Plain radiographs of early CRMO show osteolytic lesions with periosteal reaction. MRI is highly sensitive for detecting active CRMO lesions in bone.2

Although local and systemic increase of tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a) has been documented in active CRMO, the pathogenesis is poorly understood and there remains no curative treatment.5 The goal of therapy is pain control. No single agent has proven consistently

effective. First-line treatment with NSAIDs is helpful in about 80% of cases.1 Other treatments include sulfasalazine, methotrexate, corticosteroids, and infliximab. In refractory cases, bisphosphonates have been used to inhibit bone resorption and provide an anti-inflammatory effect by suppression of TNF and IL-6.2

Most patients have resolution of symptoms post-pubertally. A quarter of patients have persistent disease and risk permanent bony deformities.1 This highlights the potential devastating implications of a delay in diagnosis. A patient with presumed osteomyelitis and sterile cultures requires careful surveillance for other foci of bone inflammation and enthesitis, which when present should raise suspicion for CRMO and prompt referral to a specialist.

In this teenage boy, the inflammation in areas of bone and the entheses noted on the radiograph of the unaffected left knee prompted referral to a rheumatologist who confirmed the suspected diagnosis of CRMO. After the initiation of NSAID therapy, his symptoms

dramatically decreased.

1. Catalano-Pons C, Comte A, Wipff J, et al. Clinical outcome in children with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:

1397-1399.

2. Meittunen PM, Wei X, Kaura D, et al. Dramatic pain relief and resolution

of bone inflammation following pamidronate in 9 pediatric patients with persistent chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Pediatr Rheumatol

Online J. 2009;7:2.

3. Eleftheriou D, Gerschman T, Sebire N, et al. Biologic therapy in refractory chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis of childhood. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1505-1512.

4. King SM, Laxer RM, Manson D, Gold R. Chronic recurrent multifocal

osteomyelitis: a noninfectious inflammatory process. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;

6:907-911.

5. Deutschmann A, Mache CJ, Bodo K, et al. Successful treatment of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis with tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockage. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1231-1233.